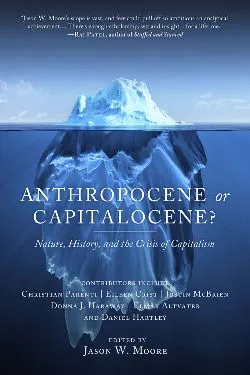

Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Necrocene, Chthulucene–what should we call the current geological era?

All of the contributors in this anthology push back against the concept of the “Anthropocene,” and they are nearly united in the view that this simply reinforces human hubris in trying to mentally separate itself from nature. Instead, they offer a few different ways of thinking about the subject, and the essays within are a bit inconsistent.

The first–and most frequent–formulation in the text is the “Capitalocene.” The sense with this conceptualization is that Capital, as a system, is not merely about “economics.” That is, it isn’t just market or trade or finance or anything like that. Instead, the emergence of capitalism coincided with–and is responsible for–our attempts to divide “nature” from “society.” Many of the authors make the compelling case that this doesn’t begin with industrialization, as we tend to think it does. Instead, the same logic pushed forward “the four cheaps” in the Early Modern period: cheap labor (i.e. slavery), cheap food, cheap energy (e.g. wood, coal), and cheap raw materials. Jason Moore brings forward evidence that the total deforestation of the European continent actually began in the long sixteenth century, and the British relied heavily on coal even before the production of the steam engine. Moreover, they correctly see Capital as a coherent system that is caused and driven by humans, but runs on its own logics, so “anthropos” isn’t necessarily the correct word for it. It historically was not–and currently is not–all of humanity driving these seismic shifts: it’s those with access to capital.

The second formulation–the necrocene–I find much less compelling. Justin McBrien dedicates much of his essay to unpacking this idea, which he ties with extinction. It is true, after all, that we are living in the Sixth Great Extinction. Even more significantly, we are driving the Sixth Great Extinction. The issue, I find, is that it removes our responsibility from the terminology. Okay, we are in the epoch of necros, but that doesn’t say any who is doing the killing. It allows it to be conflated with epochs like the Permian Extinction, or that at the end of the Jurassic period. This is exactly what we are trying to avoid.

The third formulation–the Chthulucene–is interesting. This is Donna Haraway doing the sort of work that Donna Haraway always does. It’s sophisticated, it’s playful, and it’s smart. The terminology Chthulu obviously comes from the Lovecraft mythos, but she unpacks it a bit. For instance, Chthulu’s name is a reference to the Greek chthonic gods. That is, the gods of the land. Rather than anthropos looking up to Olympus, she pushes us to look back downwards at terra, Gaia, and take care of what we have. She also plays a bit with the image of the tentacle–so widespread in Lovecraftian fiction. I didn’t know that the word “tentacle” comes from the Latin tentāre: to feel, to hold, to touch. She urges us to break bread with (cum pānis) our companion species, take care of one another, and live together–recognizing our embeddedness with one another. At least, I think that’s what she’s saying. She expanded upon her arguments here in Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, but I’m not sure that I fully got them. As much as I enjoyed her wordplay and emphasis on how intertwined all of us are–that is, the more-than-human world–I’m not sure that “Chthulucene” is a good word to refer to an epoch best understood as humans pushing the planet to its limits, destroying everything that can’t be sold for a profit.

Thus, I’m in most agreement with those who argue in favor of the “capitalocene.” It strikes me as much more suitable than the “Anthropocene,” although I’m not wholly opposed to the latter terminology either: it allows us to hold ourselves responsible for what we are doing to our planet. Still, it is also true that it is a result of the same logic that allows us to see ourselves as “separate” from nature.

This book is a short read, and all of the contributors have something important to say. For those interested in science and technology in society, radical politics, and our current moment, it’s worth taking a glance over this work. Even so, I don’t think it’s one that’ll stick with me the way that some other books do.