This is a very important book, and it is especially so for me, as the years covered here were politically formative.

I remember when the “protest decade” began, although I was far from any of the action. I was 15 years old—in a suburb of Chicago—when the Tunisian Revolution broke out. I knew very little about it at that time, only that it seemed to be big, and it quickly spread to Egypt and the rest of the Middle East. I was part of a small organization where we—all teenagers—discussed and debated current events.

Today, I live in Tunis, and see the aftermath of the Revolution totally differently than I had back then. Of course, my early understanding of it was filtered through the ever-present (and honestly hegemonic) concepts of “democracy” and “freedom” as understood by Washington. It goes without saying that this wasn’t the full story. One of the most widespread slogans of the Revolution, was “Bread, Freedom, Dignity, Nation” (it sounds much better in the original Arabic: “Khobz, Hourria, Karama, Watania”—“خبز، حرية، كرامة، وطنية").

Since then, there has been a worsening of economic conditions, social and political backsliding, and widespread discontent.

How did this happen? It almost seems to be the exact opposite outcome from what early revolutionaries intended. This result, Bevins assures us, has been a global trend.

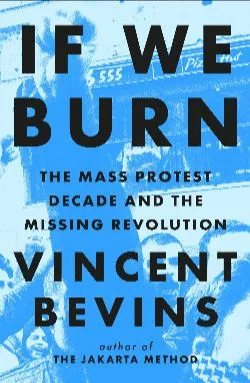

In this book, Vincent Bevins offers a solid, journalistic account of the global “protest decade” from the outbreak of the Tunisian Revolution in December 2010 to the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic in early 2020. His coverage is quite broad, and he covers protests that broke out across the Arab world, Ukraine, Chile, the U.S., Western Europe, Turkey, Korea, Indonesia, and more. The bulk of his attention falls on Brazil, where he reported for the L.A. Times and participated in the Free Fare Movement.

While his discussion of specific protests is good, he is at his best when he discusses technics. There is considerable attention given to the tactics that the protesters of the 2010s used, which might be generally grouped under the umbrella category of “horizontalism.” For the most part, these social movements tended to the Left, but rejected intense organizational structures, which were derided as “Leninist” and have been dismissed as insufficiently egalitarian.

The problem, Bevins argues, is horizontalist movements have tended to come with a fatal flaw: horizontalist movements tend to lack a single coherent idea that all people unify around. Instead, they are open to everyone, and there is little decision-making capability. As a result, the message becomes diluted, at best. In worse cases, social movements are seized by competing—and better organized—political actors. There really isn’t such a thing as a true political vacuum.

I think Bevins is right. In Tunisia, for instance, the Revolution was not really about one thing, but the most important cause—in my view—was economic justice. Of course, there was significant opposition to RCD, but the Revolution was really rooted in the marginalized interior, where economic prospects were slim (the “bread” component of the slogan). This was exacerbated by the tendency by state officials to humiliate the marginalized (thus, the need for dignity). However, by the time it reached the capital, more bourgeois groups—lawyers, journalists, and so on—made their own claims and emphasized the “freedom” of the slogan. Organized groups—essentially becoming the Troika—seized the Revolution for their own ends, and marginalization continued.

This is all to say that crowds are great at negating established power structures, but they are fundamentally incapable of generating positive transformation.

Throughout the book, Bevins also dwells a bit on the question of “the day after.” In Tunisia, Egypt, Brazil, and Chile, social movements were successful in creating a necessary rupture, but there was no plan for what was to happen after the Revolution succeeded. In all countries studied here, the limited successes won by activists were rolled back. In fact, reaction tended to be stronger than activist forces, so now conditions are often worse than they were when the “protest decade” began in 2010-11.

Bevins views mirror my own about this, and—although I’ve always been one of those more aloof, academic times hesitant to take to the streets—I’ve come to believe that some sort of quasi-Leninist organizational structure is absolutely necessary for social change. Even reform via establishment mechanisms tend to produce better outcomes than horizontalist social movements.

I apologize if this comes across as harsh: it’s all too easy to be a critic when I’m not the one doing the work, and I want to use this last paragraph to express thanks to all of those who really pushed for social change via horizontalist methods, regardless of country. Occupy Wall Street coincided with my initial political awakening, and I’ve learned so much from those who are far more courageous than I am. Social change requires taking risks, and the activists on the frontlines deserve our deepest gratitude.