Barcelona, 1453.

Barcelona, 1569.

Barcelona, 1610.

Barcelona, 1905.

Barcelona, 1936.

Barcelona, 1942.

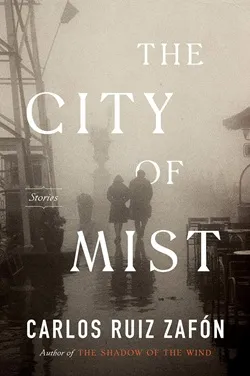

Carlos Ruiz Zafón’s The City of Mist is a book about Barcelona. It is a collection of interlinked short stories that take real historical moments–Miguel de Cervantes’ publication of Don Quixote, Antoni Gaudí’s proposal for a skyscraper in Manhattan, and the city’s bombardment in Spain’s civil war–and gives them a fantastical, Gothic spin. There are dragons here, ghosts inhabit the city, too, and there are vampires (or something akin to them) as well.

Ruiz Zafón has a few touchstones that appear in many stories: Gothic angels in stone, melancholic women in white, and sheer possibility of a city that never became. There is an immense sense of loss, which seem to me to be deeply associated with the death of Barcelona’s revolutionary project. Class plays an important role in many of these stories, and we readers see the necessity of the urban structure’s transformation. Yet, the revolution failed, and all that remains is mist and melancholy.

Ruiz Zafón’s image of Barcelona is decidedly different from the way it advertises itself today: after all, is Barcelona not a stunning, sunny, avant-garde city? From our vantage point, it is! I love Barcelona, and I believe it to be Spain’s finest city. Yet, Ruiz Zafón assures us that there is something lost in this image of it. Barcelona is a city that has suffered, and continues to suffer, under the baggage of its immense, weighty past.

All of the stories here are excellent, although the single best must be “The Prince of Parnassus,” Ruiz Zafón’s fictionalization of the production of Don Quixote. But, this collection is unusual in that there is not a single mediocre story: they are all beautifully written and are composed with the magic that flows through the city’s broken cobblestones.

While all of the stories stand on their own, they are also intertwined. The first story, for example, are about the childhood experiences of a young boy named David Martín and his beloved Blanca (the “woman in white,” if you take the name seriously), while the second story is about a young mother giving birth as she dies… to a son named David Martín. We learn about a Raimundo de Sempere, who receives plans for a labyrinthine library from a refugee after Constantinople falls. In another story, an Antoni de Sempere befriends a youthful Miguel de Cervantes as he arrives in the city from Rome. An astute reader will see the familial relation between these two Semperes.

The stories are so deeply intertwined that the primary character is best understood as Barcelona, which has agency over the many characters who inhabit it. Barcelona is an eternal, haunted city, and I only wish I could spend more time reading it through Ruiz Zafón’s mind. May he rest in peace.