Spoiler Alert

This content discusses key plot points, resolutions, and major surprises. If you prefer to experience the story first-hand, bookmark this page and return later.

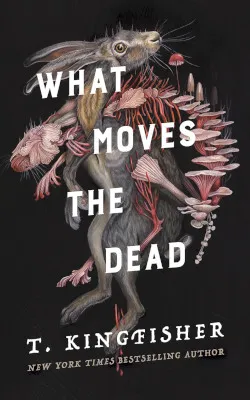

I picked up What Moves the Dead because I wanted to join a local book club, and this is their next read. T. Kingfisher is a popular author, but I had never read any of her books before.

Wow. I was impressed with it. The premise is quite simple: How might we expand, or perhaps re-read, Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher.”

I had always read Poe’s story through the lens of a newfound American identity: the House of Usher represents European states and systems. In other words, the story is a way for Poe to poke at European aristocracies and say, “While they’ve had an illustrious past, their days are numbered, and there is no way forward for them.” Both Roderick and Madeline were destined to die, along with their house. There is nothing anybody else can do about it.

What Kingfisher does here is quite different.

As in Poe’s story, Madeline is on the verge of death, and Roderick suffers from an “illness of the nerves.” Instead of offering a harrowing, gothic tale about social systems, Kingfisher provides us with a story about possession. Possession stories always fascinate me. I think they are a way of talking about human agency in a wondrous, awe-some, or grotesque manner. In this novel, rather than being possessed by ghosts or demons, Madeline is possessed by a fungus that grew in a tarn.

Kingfisher’s note to the reader–at the end of the novel–is eye-opening. She mentions in it that she was fascinated by how often Poe refers to mushrooms in his story; this is especially notable with how short the original story was. The author, for her part, was able to incorporate Poe’s mushrooms with recent advances in mycology (which are fascinating and have made it into the mainstream).

When I grew up, I thought about mushrooms as lifeforms similar to plants. They seemed to have a stem, and might have been comparable in my young mind to miniature bushes or trees. I knew that other fungi existed–I mostly thought of lichen and mold. I had never given it too much thought, and never considered that yeast was also a fungus.

Recent advances in mycology point to fungi being wholly different from plants and animals. They exist in colonies and fungal cells are largely undifferentiated; that is, there are no “brain” or “heart” or “skin” cells. Additionally, many fungi reproduce asexually. In other words, there are not two “parents”: there is one. The spores released by these fungi are identical to the parent. They communicate through chemical signals. They come in many forms.

If we limit our understanding of life to animals, plants, and individual cells, fungi look weird. They are alien. As a result, they make for great cosmic horror.

I wouldn’t characterize Kingfisher’s book as cosmic horror, but it does draw heavily on the Weird tradition (which is often symbolized by a tentacle; cephalopods, too, seem alien to us, even though they are animals). We are forced to the realization is much stranger and far more terrifying than we ever thought it could be.

Kingfisher’s world has enough flesh to be immersive, in spite of the book’s brevity. Thanks to well-placed exposition from the perspective of the narrator, Alex Easton, and discussions with other characters, we learn a lot. Even so, this isn’t world-building from scratch, building us a whole new universe. Instead, learning about Gallacia and Ruravia is comparable to learning more about actually-existing places and customs through realistic novels or journalistic accounts. It is as if I read a travel editorial by a Bulgarian author; they might complain about some things, sure, but it isn’t too much more than regular griping. I might find it odd that the editorial writer discusses how the rabbits walk funny; but, realistically, my eyes would continue drifting across the page without a second thought.

What Moves the Dead is also interesting in terms of genre. I saw it marketed as “dark fantasy,” but it is much better characterized as “weird horror.” There were moments in the last act of the novel–especially when I was reading late at night–that I felt frightened. My fear came less from the events of the novel than the “vibe.” Imagining wispy hyphae; breathy, hollow laughter; and jagged locomotion offered a wholly “xeno” image. My problem with reading novels like this is–instead of taking for granted that it is fiction–I really do wonder, “What if the world were like that? What if this were true?” Call it an overactive imagination or what you will, but it is how I engage with texts. And engaging this novel through that lens generates a horrifying view of reality. What else might we not know?

Kingfisher’s story is structured as a classic mystery; she drops clues throughout the book, allowing us to piece it together. I had figured it out quite early, somewhere around the 90 page mark, when Easton goes hunting for a hare. There is enough material here that the reader will feel proud of herself when she solves it, but it could have used more misdirection. If you paid attention, everything was quite clear.

What really impressed me is Kingfisher’s attention to detail. Of course, the clues that Kingfisher leaves lying around are tied back into the mystery effectively. For instance, when Madeline’s “other” sleepwalks, it has trouble pronouncing certain sounds, and we learn at the end of the book that the fungus needed to learn how to talk. Fungi don’t communicate the way that humans do. But, more significant to me was the content of that early hint. Madeline’s actual dialogue is:

“One,” she said. “Two … thhhhreee … ‘our … ‘ive … sixsss …” She paused as if thinking. “Se’en … eight … nnnine … te-uhn.” She looked at me. “Goooood?”

Earlier, she had trouble saying “M” sounds. So, the fungus is unable to pronounce “F,” “V,” and “M.” All of these are labial consonents. In fact, they are all of the labial consonants that would have been spoken in alter-Madeline’s sentences. Kingfisher’s choice about which sounds the fungus finds difficult is highly logical; there is nothing random here. I’m not sure that I could have pulled that off in a story, and it is detail like this that makes What Moves the Dead so alive.

The end was satisfying, although I did have mixed feelings about completing the book, simply because I wanted to spend a bit more time with constructions of the author’s imagination. What Moves the Dead is an excellent introduction to her oeuvre, and you can be sure that I will be reading more of her books.