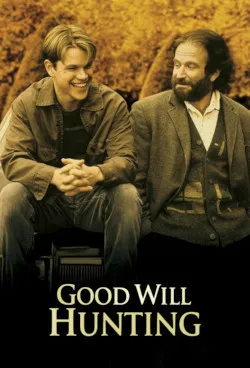

Good Will Hunting was picked by my fiancée for us to watch together, and I could not have been more impressed. I’ve often heard that this film is one of the “greats,” but the premise struck me as uninteresting. I could not have been more wrong.

The titular Will Hunting (Matt Damon) and his friends (one of which is played by Ben Affleck) are working-class kids from South Boston; they spend their time laboring at blue collar positions and hitting the local Irish pubs. They get in fist fights with other young men around the neighborhood and aggressivly hit on young women. They have a crude sense of humor and have trouble envisioning a better life.

But Will Hunting is different. He’s a prodigy who happens to work as a custodian at MIT. When a prominent mathematics professor, Gerald Lambeau (Stellan Skarsgård) pitches a currently-unanswered problem to his students, Hunting anonymously solves it. However, when the professor attempts to reach him, Lambeau discovers that Hunting is being threatened with prison. He works out a deal in which Hunting will be released in exchange for one-on-one time working with Lambeau, as well as weekly therapy.

Mathematics problems, Hunting can solve, but therapy is another story. After Will antagonizes therapist after therapist, Lambeau reaches out to an old friend–Sean Maguire (Robin Williams)–and launches the greatest father-son relationship in the history of cinema.

While the plot and cinematography of the film are both excellent, what really stands apart is the way the movie grapples with masculinity in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Hunting is an orphan and his “brothers” are his friends. He’s been humiliated, spat on, and beaten. He believes he’s seen it all, and he lives better realities vicariously through books. Yet, he has never physically left Boston.

In the United States and, I think, much of the world, we extol book-smartness as the epitome of intelligence. Even so, many prefer to celebrate the “school of hard knocks” as the greatest academy. Will Hunting has both. Yet, it is not enough. Quite the opposite, in fact. Rather than live the benefits of these two curricula, Will suffers.

Throughout the film, Maguire manages to reach through Will’s iron-thick scales and demonstrate to him what it means to live a full life of intimate connections. While Hunting does have his gang, their connection–while real–does not provide any of the boys with a sense of who the others are. In fact, it is only at the end of the film, when Ben Affleck’s character speaks intimately with Will, that we get a sense of the person under the armor.

Time and time again, Will sabotages connections: he insults Maguire (and his wife), he pushes away the woman he loves, and his friends remain a small clique. Yet, we see him develop into a caring young man with a sense of purpose.

This film is important, because Will Hunting is every man in America. In fact, I would encourage young men–now as much as 1997–to watch the film. Will Hunting’s story should not be pitied as “how people become when they have difficult backgrounds.” Nor should we pat ourselves on the backs for being 21st century emotionally intelligent men. Whether we are or not, the large social structure in the US facilitates the creation of Will Huntings, and all of us are at risk.

How often do we not talk about ourselves out of fear of sharing something vulnerable? How often do we sabotage ourselves, even when we do know what we want? How often do we get lost in the idea of “what it means to be a man?” I do it, and I know that most of my friends do it too, as hard as we try to be open, sensitive people.

In fact, this self-protection is so deep that it took me ages to ever get to know my father or brother. We would do things together at times, but we never really talked. I had to learn to ask questions and share my own experiences. When I disagreed, I learned it better to talk through it with them while remaining open to hearing about their perspectives. Doing so is not a matter of changing my mind–I have different values and ideas about the way the world should be–but by adding nuance and bringing forth serious comprehension of subjectivities outside of ourselves.

Some people have built such thick barriers to protect their past hurts that they live out the politics of resentment through pick-up culture, the “red pill,” and Andrew Tate-ism. Others have few wounds, but play the “scientific” sexism game and pretend to bolster their worldviews with “logic” (and, it is worth noting, that the world of emotions is incomprehensible within such a cosmos).

Robin Williams’ character offers an off-ramp to toxic masculinity and provides lessons to those of us who want to help others, even as we travel along this path. To reach other men, we must foster trust and vulnerability; I think every single one of us craves this, but we are afraid to go there. It is only by asking questions and being open about our own experiences that the walls will come down, and these things take serious courage.

Good Will Hunting likely will not immediately change minds, but it might be the push needed to open up questions. To become like Will Hunting or–better yet–Sean Maguire is a long-term process that demands patience and introspection. I can’t think of a better way than Good Will Hunting to introduce this path to others; it’s a must-see.